What a six months it’s been – AIs and chatbots have hit the headlines and hijacked the zeitgeist!

It’s hard to go a week without seeing a spruiker or a detractor (or several of each) claiming everything is about to change for the absolute best or the absolute worst.

And the “silicon entities of the hour” seem to be ChatGPT and Bard, Large Language Model (LLM) AIs which are causing quite a stir with their convincing responses to plain English prompts.

I’ve been around IT long enough to be able to say with certainty that AIs are nothing new.

While my exceptionally switched on IT teacher in the 80’s was focussed on the integration of various devices such as phones, computers, cameras, TVs/VHSs, etc. into multi-purpose devices (which we now carry in our pockets), AIs were already a “buzzy” topic of conversation in IT circles.

But the running joke has been that “true AI is only five years away” – no matter when you ask.

Now, between image generators like DALL·E (which came to prominence in 2021), website and call centre chatbots, and now LLMs, it seems like the five years is up, and the “Age of True AI” is upon us…

Or is it?

OK, I admit it – I’m one of the skeptics…at least in relation to the utility in Strata (and many other technical fields) of currently available LLMs. But let’s step back a little.

AI, “Artificial Intelligence”, is a loaded term – the first part is really easy, but just what are we going to claim or accept as an “intelligence” born not of flesh.

Personally, I prefer AGI: “Artificial General Intelligence”, which, according to Wikipedia, is “a hypothetical intelligent agent which can understand or learn any intellectual task that human beings or other animals can” (my emphasis). I can live with that definition.

And, based on that definition, what we’re seeing with DALL·E, ChatGPT and Bard is anything but such an “artificial general intelligence” – it’s not even a semblance of a basic intelligence!

These latest chatbots seem convincing, sure – but all they’re really doing is providing something that looks like the right answer. Sometimes the similarity to the right answer is striking and you’d be hard pressed to notice a difference. Sometimes…not so much.

Here’s an exercise I’d like you to try:

- Think of a subject matter you have a large amount of technical knowledge in (it doesn’t have to be strata);

- Think of one of the most technical aspects you’re familiar with in this subject matter;

- Think of a question regarding this particular technical aspect that you’d like to ask another expert in the field to compare notes with;

- Go to chat.openai.com and login (or sign up if you don’t already have an account);

- Paste or type your question into the prompt field; and

- Review the result.

What you’re going to see is one of three things:

- An impressively correct exposition on the question – “top of class” stuff you can’t fault;

- Something which is close (for various values of “close”), but “no cigar” territory for those in the know;

- Something which is so wildly stupid, you can’t understand how this thing was ever considered “intelligent”. You want your money back! (I hope you signed up for the free version.)

Part of the problem is that for the second and third cases, these LLMs will rarely say “I don’t know”, or “maybe” – they will usually give just as convincing sounding an answer as what they provide in the first grade of response. And, for reasons I touch on below, the first type of response is just a fluke!

And even on the odd occasion ChatGPT says it can’t answer a question, it can often be tricked into doing so, and once again, the result of that tricking will fall into one of the three categories above.

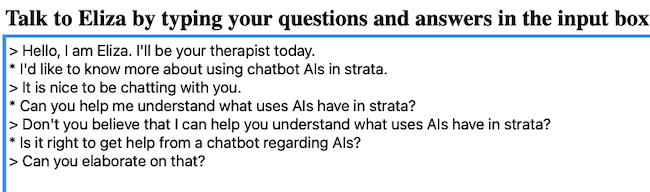

When I was first of companies considering ChatGPT use in strata, I asked it “What is the process for getting renovations approved in a strata building in NSW?” – this was, I expected, a straightforward prompt given we’re over 7 years into the new regulatory regime in NSW.

I won’t quote the whole answer on this page (you can find it here), but my rough assessment at the time was that it was about 10-20% right. Pretty atrocious, frankly. I’d be embarrassed if anyone I managed sent that response to a client.

The next day, after mulling on it further and wondering just where it all went wrong (I sorta suspected, actually), I amended the prompt with a simple tail-end addition (highlighted): “What is the process for getting renovations approved in a strata building in NSW, with reference to the Act?”. The first paragraph of the new response was telling:

“In New South Wales, the process for getting renovations approved in a strata building is regulated by the strata schemes Management Act 1996 (NSW) and its associated regulations.”

Bingo!

No wonder it was up to 90% wrong: It was referencing 27 year old legislation! But when you sign up or login it says its knowledgebase stops late 2021 – how could it be so wrong/out of date?!

This is where modelling, prediction and weighting come in. What ChatGPT did, based on the information it was trained on, was provide what it calculated/predicted was the most likely/suitable response from weighted information sources. My amendment just got it to admit where that weighting lay – on information sources tipped towards the 1996 Act.

And the prompt can actually affect the weighted selection of sources, so framing my question differently may well have resulted in the 2015 Act being used, with its “cosmetic”, “minor” and “all other” (aka major) renovation definitions. Maybe. This is why I said above that these systems may fluke the right answer.

I tried again by asking for a letter to an owner regarding the major renovation approval process, and, to “force its hand”, my prompt referenced the 2015 Act explicitly, but it still took several refinements to get to the point of being (maybe generously) 75% acceptable (you decide) and ready for me to consider editing and sending it to someone…perhaps. It might have been quicker for me to just type something up myself.

Don’t get me wrong – these models will have continuing improvements (the above examples used ChatGPT-3.5, ChatGPT-4 has since been rolled out), and these sorts of “gotchas” will become less and less prominent, even in deeply technical fields such as strata. If I started these tests in five years’ time, the results would be very, very different.

Additionally, it may be possible to train the systems now by providing a body of knowledge before you ask your “real question”, but you’d have to know the right type of training material to provide, then find or write it in a way the AI can ingest it. At that stage I’d have to ask, “Just what are you really gaining?”

But what I’m really trying to get across is that we’re nowhere near the stage where we can rely on these bots in strata (and other deeply niche technical fields), and in addition to that, there are several other important issues with using these AIs to keep in mind:

- Where is your data going?

Your prompts are almost certainly going overseas – does this match your business’ data sovereignty policies? Or government requirements? Beware of including personally identifiable information (PII).

- How will your data be used?

“In the AIs’ training data” is the short answer. Will the information you provide to these AIs end up forming part of future knowledge bases that answer prompts from your competitors? Maybe? Probably?

And what are the privacy implications of sharing customer data with external parties in this way? Scary, if you ask me.

How will you ask your clients for permission to use their data in this way?

- Whose base data are you relying on to answer your prompts? Do you get to see what data the LLM was trained on?

I’ll save you Googling that one – the answers are “We don’t know” and a resounding “No”, respectively.

All the developers of these AI systems closely guard their LLMs’ training sets as proprietary information. And sometimes, they have don’t even have a licensed right to use that information in the way they have in the first place!

Would you be happy basing business decisions or drafting customer responses on such potentially spuriously-sourced information?

- How is the information weighted to appropriately form answers? Who chooses the weighting?

Like the last last question – we just don’t know. Maybe an algorithm (that we don’t get to see)? Maybe guided by humans. Maybe by providing additional material…maybe not.

- Do you trust beta software?

All of these systems are under active development, are early stage versions (think “proof of concept”), and may (as shown above) generate dubious content you cannot base responses to customers on. When will they be ready for “prime time”? And who decides when they are? Another set of “We don’t know” questions.

So, after all that, do actually I see any utility here? Sure – but you just need to assess these systems’ suitability for your use cases.

For generalist writing tasks, these bots may provide better output than some people can provide. Great, I say go for it for such non-technical use cases.

But if I were running a strata management or other technical field company/consultancy, I’d be testing a heap of prompts to see what sort of responses I might expect before going anywhere near a general rollout, and I’d certainly want my staff to be protecting the company by:

- Carefully reviewing responses before sending them to any external parties – this review is best carried out by someone knowledgeable in the field, who may or may not feel the bot-generated content has saved time over creating the response themselves;

- Assessing the business risk of relying on such external “(fake) expert systems” we have no ability to review the inputs of – what are you prepared to stake your business’s reputation (and liability!) on?;

- Ensuring personally identifying information (or information about strata schemes) is removed from prompts – but this means such information needs to be stripped out or obfuscated in prompts, then placed back into responses;

And that’s after giving all team members prompt generation training (including assessments), determining best use cases (and use cases to avoid), and creating an auditing framework to allow periodic review of usage and suitability.

We are going through a time of rapid awareness and uptake of these technologies, and they’re being applied in new and interesting ways (e.g., meeting summaries in Microsoft Teams, aiding internet search engines to generate responses, automating computer programming) – but all of these uses come with caveats similar to the above, and we are about to see a wave of partially (or completely) incorrect information flooding our infosphere.

I believe our organisations and management teams have a lot of “checking sources” and “trust assessments” ahead of us externally, and a lot of “use case soul searching” internally.

Despite the length of this post, this is all just the tip of the iceberg, both in the use of these “AIs”, and in the critical assessment of them. I would love to hear your thoughts – what are you using these AIs for, and where have you seen things gone off the rails?

Please comment below, comment or message me on on LinkedIn, or reach out directly if you’d like to…well…chat. I promise it won’t be a chatbot replying!

And don’t forget to check out my introduction and About page!

Like this:

Like Loading...